The answer: A LOT.

I decided to do some very rough back-of-the-napkin math to understand spending in the CF space because occasionally I come across a strange fundraising appeal that solicits donations for cystic fibrosis research on the basis that the US government does not fund research efforts for the condition. If you run in CF circles on social media, I am sure you’ve seen them, too.

While the thought is noble, those fundraising appeals are not the truth. Far from it, in fact.

The federal government does provide capital for research into cystic fibrosis and it’s a heck of a lot of capital. From 2008 to 2019, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), “the nation’s medical research agency,” has averaged a little more $86,000,000 per year towards research grants for cystic fibrosis.

…and that’s just for the named condition.

If you include funding for medical research into antimicrobial resistance, diabetes, osteoporosis, and a slew of other common CF related conditions that may tangentially touch our lives, the number quickly balloons by a magnitude of hundreds of millions of dollars, but for the purposes of this post I will leave that out.

NIH provides funding for basic laboratory research, clinical activities, and things that you may not even know are happening in academic medical centers and labs across the country.

The tool linked above is pretty cool and will show you the amount of capital NIH provides based on individual diseases. Sickle Cell Disease researchers, for example, were awarded $104 and $139 million worth of grants in 2018 and 2019, respectively.

Of course, the US government is not the only group that provides funding for CF research. Charitable trusts, endowments, nonprofits, institutional foundations, the biopharmaceutical industry, Wall Street, and others all contribute to cystic fibrosis research and development. When you consider global efforts, the amount poured into CF work is likely enormous (and far beyond the scope of what I’m conveying here). If I had to levy a guess, the collective biopharmaceutical industry operating in CF is probably the leader in the clubhouse alongside the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. In total we’re probably looking towards at something close to a billion dollars per year (a rough guess, of course, give or take a hundred million or so) across the entire above listed ecosystem.

The cost to develop a single drug runs at about $2.6 billion depending on who you ask. Imagine that number as the magic number these companies need to drive towards when an idea sprinkles in from an academic lab. That company needs to translate the academic’s idea, test it to make sure it’s safe, and then license it. Of course, drugs are not the only things that improve the lived experience.

My curiosity led me down a rabbit hole of financial statements (that I’m not super proud of because it wasn’t exactly how I planned I would spend my Tuesday night, but I did it anyway) to see if I could benchmark NIH’s giving.

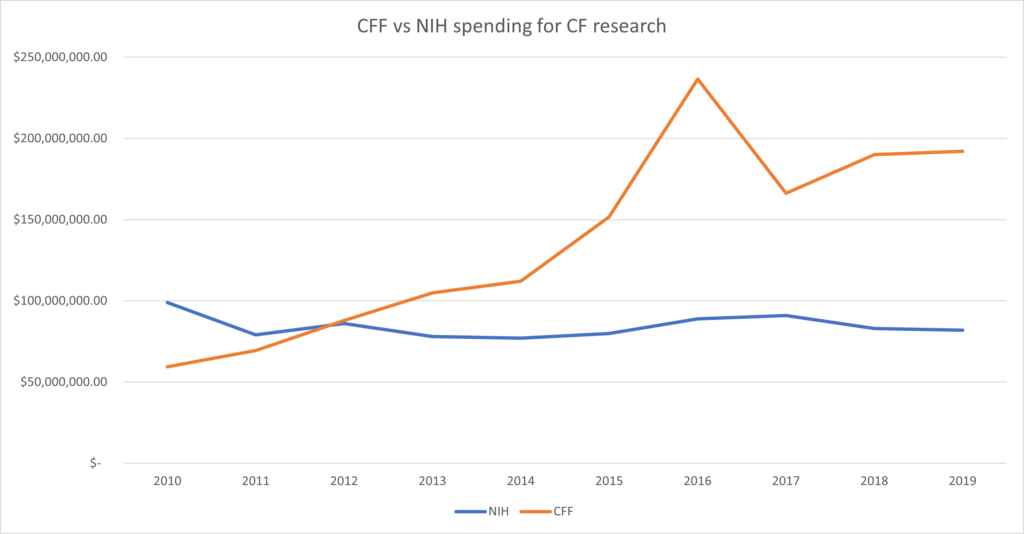

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation is undoubtedly the gold standard for research awards in cystic fibrosis – both for academic and industry partners. The CFF lists several line items in their financial statements (linked below) for medical programs like therapeutic development, research grants, clinical research, clinical grants, fellowships, and quality improvement projects among other overhead costs like employee salaries. I parsed out the project awards as best I could away from what I considered overhead and revealed that from 2010 to 2019 the CFF contributed about $137,000,000 per year towards medical research and work. Notably, I included medical care in that number (which represents support for CF clinics, and does stray from the lens of NIH awards) and did not include patient support packages based on how I define “research.”

I also took a quick look at the CF Trust’s financials (linked below) to see what contributions look like overseas. Their disclosures are obviously in Pounds Sterling, so after a quick conversion to dollars, I found that they are contributing close to $9.5 million per year from 2015 to 2019 (note, their fiscal year differs from the one represented in the CFF’s disclosures, so I tried to allocate funding to the calendar year January 1 – December 31). Over the same period, the Trust spends about $875/patient in research and clinical care dollars. I did not investigate British government spending on CF, which is likely significant based on the way care is delivered in the UK via a government-backed healthcare system. With some simplified strategic thinking, one would imagine that the British government sees a path to reducing the cost of care for CF patients via investing in better technology for patients.

Notably, the Trust lists “Information, Advice and Support” as part of their charitable giving and is one of the organization’s biggest line items year to year, which I am not including under the umbrella term “research.” That said it, it very well could constitute some form of research (financial statements aren’t always the most representative means of understanding what’s going on underneath the hood).

The CF Foundation’s number is incredibly impressive, but even more so when you look year to year, which then reveals the power of their venture philanthropy model.

As a reminder, part of the CF Foundation’s revenue generating model is a that they invest in early-stage biotechnology companies to build investor support for programs that may not otherwise garner the needed attention and then sell their stake. On an absolute scale, the investments into these companies, while significant, are not very big contrary to what you may think when you see these numbers. Compared with the other kinds of investors who help deliver cures and treatments to patients, the Foundation’s Venture Philanthropy (VP) model is a bit like the much-needed jumpstart for technologies. Importantly the model brings with it credibility for ideas.

On the back end of a deal, the CFF likes to sell their equity or drug royalty stakes for revenue that trumps even the very best of fundraising years many times over. Prior to the big VP deal, the CFF was spending between $2,000 – $3,000 per patient per year. More recently that number is well over $5,000/patient.

Look at the chart below, which compares NIH giving to that of the CF Foundation’s, and take a guess when one of the Foundation’s big royalty sales came through.

All in, research spend is not the only thing driving longer lives for patients. Organizations also spend for advocacy, financial assistance, patient programs and a lot of services in between. Importantly, total spend is only one metric that shows progress, and should not be considered the end all be all.