If you’ve followed my blog for the last year or so, you’ve seen that I’ve been repeatedly discussing the value of generic medicines. The brand we’ve long known as Kalydeco will soon be forced to compete with a generic equivalent, and that’s a good thing!

Generic medicines, typically, provide seemingly unlimited value to patients and society. Think about your current CF care routine. Maybe you take albuterol, the occasional oral antibiotic or hypertonic saline. These, like other classic CF medications, are generic equivalents to once branded medications. Modulators are notable exceptions (so far) because they’re so new. Generics exist, cheaply, because the exclusivity periods their branded counterparts used to enjoy have run dry.

At one time, generations ago, these drugs, like more than 80% of the entire US’s drug arsenal, were more expensive medications on brand. You can think of it like paying a mortgage against a home. For a finite period of time, homebuyers pay large monthly installments to their lender, until the homebuyer truly owns the home in full.

In June, generic Ivacaftor was tentatively approved by the FDA. The approval comes with the caveat that the drug cannot be licensed until the exclusivity period for Kalydeco comes to an end, which it should in the next couple years (Kalydeco was launched 10 years ago in 2012 and typically drugs have about a 13 year window of exclusivity).

Society values medicines, like Kalydeco, in a similar way to homebuyers valuing a purchased home.

The high cost of R&D to develop a drug compounded by the high rate of clinical (or in-vitro) failure necessitates that drug makers have a finite period to recoup their investment, win profits and then, eventually, compete against generics.

I believe so firmly in the value of generics, that I recently signed a letter to congress urging, among other issues like lowering out of pocket costs people pay at the pharmacy, them to “Empower Medicare to negotiate deeper discounts for ALL drugs ONLY AFTER 14 years on the market.”

In some cases drugs are not able to go generic (see the discussion on biosimilars like Pulmozyme in this previous blog) or in other cases pharmacy benefit managers illegitimately inflate generic drug prices through control of rebates and spread pricing (see this blog on Mark Cuban’s newest venture). We wouldn’t anticipate the modulator class of medicines to fall into the former category, but some devious PBMs might try to push patients to higher cost options to reap juicer rebates.

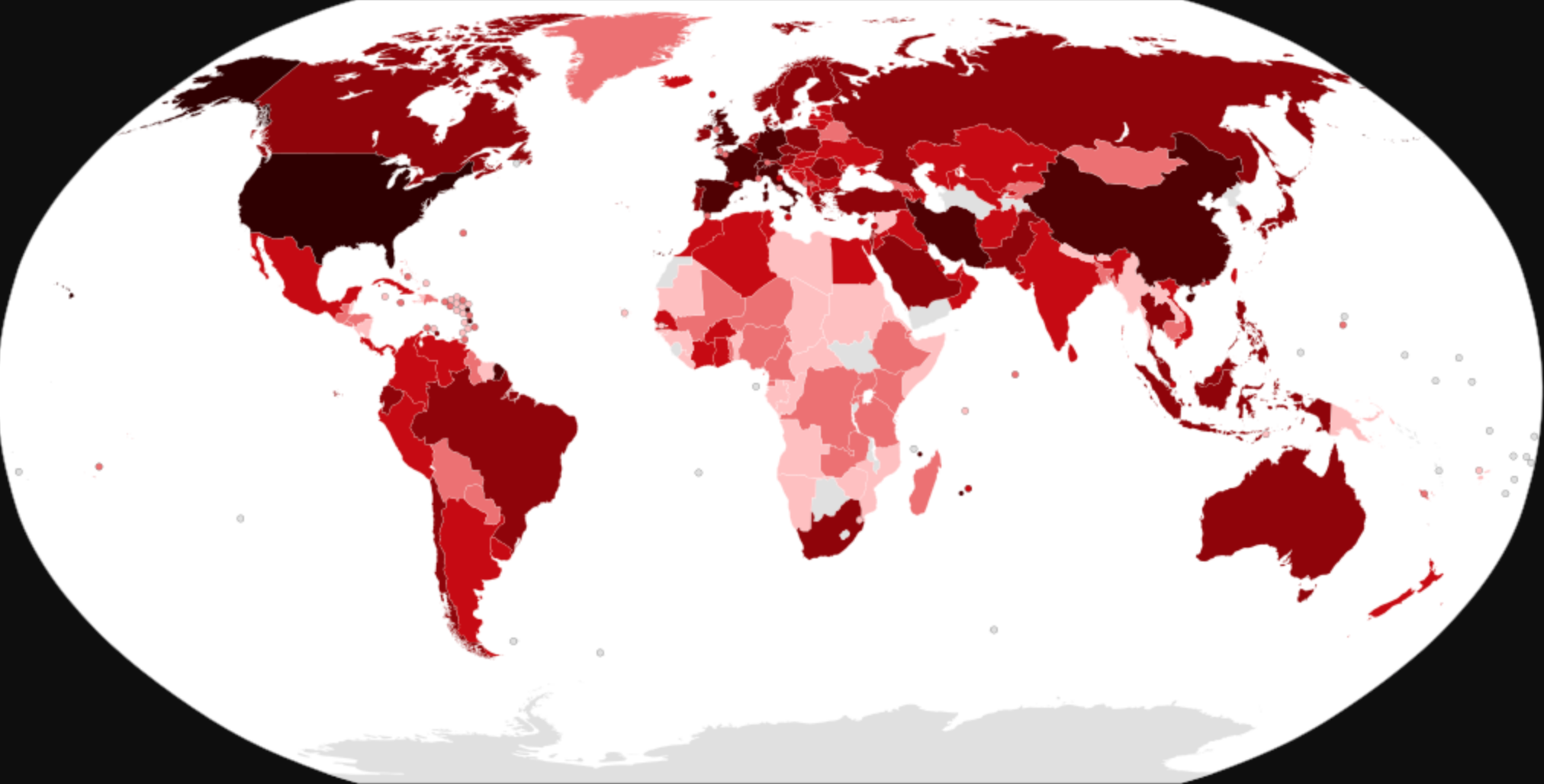

Society knows generics hold value, and so, too, do arbiters of drug affordability and availability. Outside the US, where the PBM rebate issue isn’t a problem, central bureaucratic bodies that evaluate drug cost effectiveness presumably know all small molecule medicines (like Kalydeco in this case) will go generic. How could they not? Over the last decade, nearly 90% of drugs prescribed were generic.

And yet, it’s curious that these health arbiters and academics leave genericization out of almost all published cost-effectiveness analyses. Importantly, these cost-effectiveness analyses, at least overseas, often find their way into conversations around drug access. Further, that same above linked study points to only a handful of countries that include assumptions about generic price decreases (that should infuriate you if you’re living in a country locked out from modulator access).

Or is it curious? Plainly, health affordability arbiters overseas operate from a budgetary perspective. They’re using public funds to list medicines on public formularies for their populations and have finite resources to do so. Using a delay shortens the period between the launch of a new drug and its transition to generic. It should be no wonder that access issues are suddenly resolved x-US after a few years when in reality all that’s happened is the time to generic has decreased. The delay impacts the drug maker’s total revenue, so the drug affordability arbiter gets to say it decreased the price. Patients really pay the price the form of time as a resource. Extending the time horizon on a budgetary basis would resolve this quandary.

You don’t need to take a negotiations class to understand how this works.

Want to learn more? Listen to this State of Health episode with guest Chris MacLeod:

Ultimately, generic ivacaftor is just the first of a wave of coming generics and we should celebrate that together, because it means that the CF population is actually outliving the exclusivity period of drugs that have come to our rescue.