I never thought I’d be writing about my nuts on the blog, but here we are. If you want to stop reading, I’ll give you the out and tell you the whole thing… was not THAT bad. But I am going to detail my encounters with the medical system for the male side of the IVF process in CF because there is a general lack of information available for people with CF who want to go down this road. Frankly, it is frustrating. I also am hoping to breathe a sigh to relief out there for my fellow guys with CF about the big needle. I was terrified of the sperm extraction. Mostly because I never knew what it entailed, but hopefully if I speak to it in detail, you will find out, as I did, it was quite easy.

Darcy will take to the blog soon and share what she had to do as the person without CF… which, by the way, was far more intensive than anything I had to go through. She is my hero.

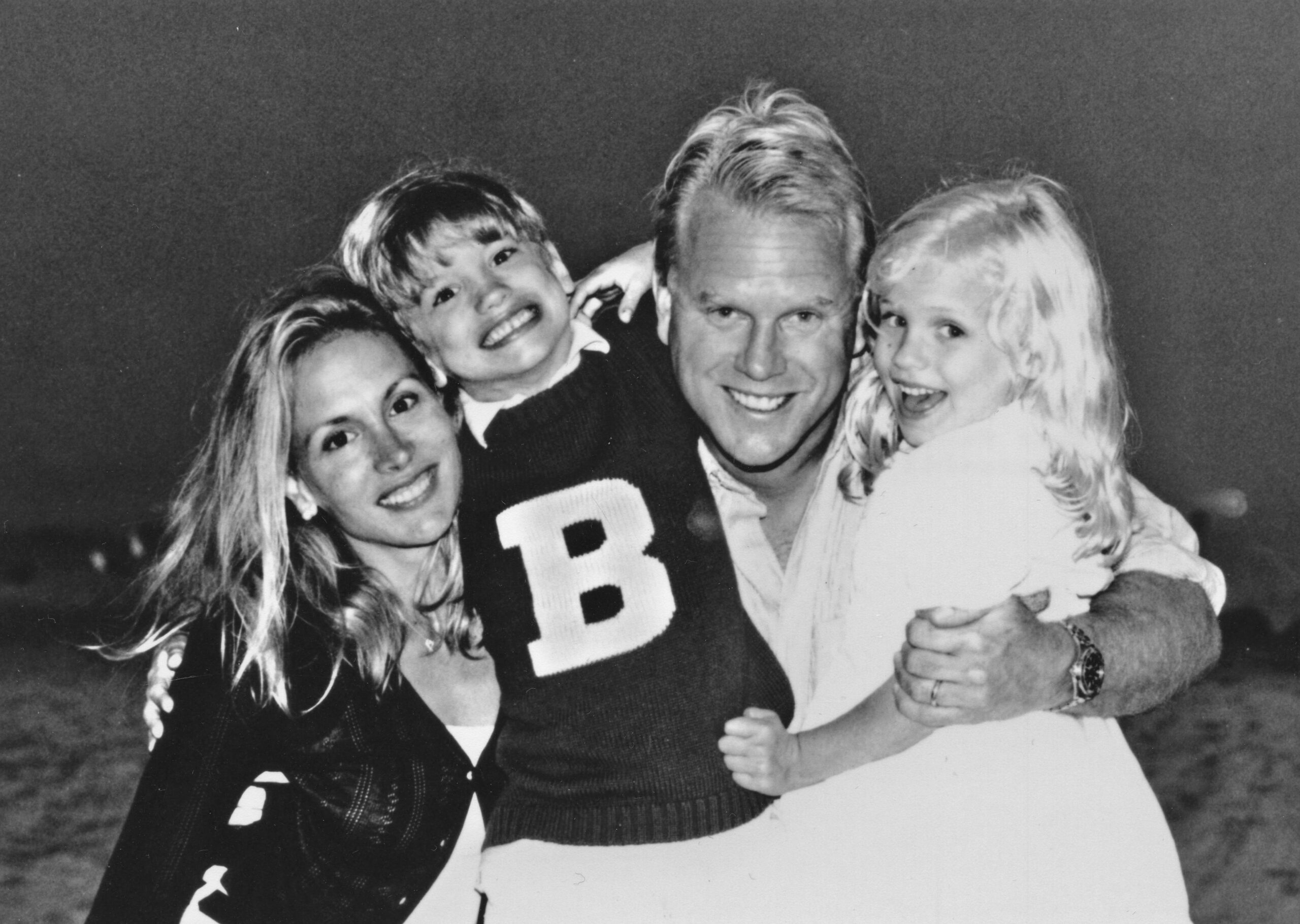

At our wedding, Darcy and I announced that we are expecting a baby boy in December! I think we’re still in shock that it all seemed to work. It has been a lifelong dream of mine to be a father, and it’s finally happening.

The news comes after IVF treatments because of the infertility that accompanies cystic fibrosis. It’s a little bit like salt in the wound – infertility – or maybe it’s just part of natural selection, where cystic fibrosis has traditionally been an inherited condition that kills in childhood. That, however, no longer needs to be the case.

Infertility strikes both men and women with cystic fibrosis, albeit in different ways. I can only speak to one side of the issue, though, anecdotally, women with CF have been telling me that there is something that has been amounting to a Trikafta-boom for pregnancies thanks to the mucus thinning qualities of the therapy. For men, however, no such benefit exists. In fact, almost all men with cystic fibrosis are born with congenital absence of the vas deferens. Infertility is actually the most common issue for men with cystic fibrosis beyond even the incidence of respiratory disease and GI disease. Notably, infertility doesn’t progress like respiratory disease. Simply, the absence of the vas deferens means that while sperm is present in the body, and thus men with CF can father biological children, it has no way of getting out.

Unless the sperm is extracted.

In-vitro fertilization (IVF) can be expensive for CF families because not all states require it to be covered under insurance (though that is starting to change in some places). I will pause right now and say that it is a long-term goal of mine to help people living with CF address the cost of the IVF.

The cost of IVF will come into play in a moment, but my first reflection on this whole thing is that because there is cost driving outside of insurance coverage, there are different kinds of incentives for patients and the various players in the space, which is a bit unlike any other part of the healthcare system. As a result, you need to keep your head on a swivel because institutions are not only competing on outcomes (as hospitals normally do), but they also compete on pricing.

Fortunately, for the sperm extraction side, most of the work is considered diagnostic and thus covered by insurance in a lot of cases. My first piece of the puzzle was last summer (August 2020), when I had to confirm I was shooting blanks. I produced a sperm sample at home, awkwardly held the cup between my legs while driving to the lab, and then even more awkwardly walked it to the lab at the local hospital. 6 hours later I was told that I was, in fact, facing infertility, which, of course, was not a surprise. I was originally told my freshman or sophomore year of high school that I was likely infertile (which is different than sterile), though I did not confirm it through testing at the time.

Not long after, Darcy did a genetic test to determine if she carries a CF gene. She does not. Beyond that, we did not perform any genetic sequencing – neither on us nor the embryos we eventually produced prior to implantation.

From there, the process should have accelerated, but the Fall/Winter surge in the pandemic slowed us down.

Because our local medical center, Dartmouth-Hitchcock, doesn’t provide reproductive urology services, I had my first consultation (virtually) with a urologist based in New York. Over Zoom, he explained what would need to be done.

First, he prescribed lab work that I could complete at the local outpatient lab. They drew for blood hemoglobin, luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, testosterone and estradiol. The tests, which were diagnostic, were looking to see if I had the right mix of hormones to indicate that I was producing sperm. Still, there is some consensus that the lab work doesn’t paint a complete picture.

In CF, there is not much reason to believe that sperm isn’t produced, but as men age these things start to dwindle a little, which is both related and unrelated to CF. Sometimes people will be put on hormone medications to boost their results – fortunately, I did not have to take additional medications.

He then explained the three search and rescue options for getting the sperm out of my balls. The three are:

- Testicular Sperm Aspiration (TESA): a long, thin needle is inserted into the testicles and sperm is removed. It is the least invasive option, though carries the most uncertainty because the urologist is essentially flying blind. Minor local anesthesia is required. The procedure is office-based. Yes, the patient remains awake for the procedure.

- Testicular Sperm Extraction (TESE): Sometimes called a biopsy, a small incision is made in one testicle (sometimes also repeated in the other), which reveals sperm carrying flesh. A small sample is then removed, which hopefully contains sperm. Some uncertainty remains with the precise location for the sample, but it is generally considered more successful and invasive than the TESA. This procedure is office-based and requires a local anesthetic and a stitch to close the incision. In this case, the patient remains awake, too.

- Microdissection Testicular Sperm Extraction (mTESE): The most intensive of the three options that is either completed with general anesthesia or local anesthesia in either an operating room of office based on the anesthetic. The doctor makes an incision in the scrotum and then uses a microscope to find sperm in different areas of the testicles before eventually taking a biopsy. It’s considered more accurate and reliable, especially for people may not produce sperm in large quantities. It is a longer procedure than the other options.

The TESA is generally not recommended for IVF because it often fails to produce enough sperm if multiple rounds of IVF treatments are required.

After the urologist explained the three options to me, things started to go sideways. He really pushed the third option, the mTESE, on me. I was sort of taken aback. My understanding of CF physiology led me to believe the mTESE would be unnecessary. In the middle of the pandemic I had no desire to go through something far more invasive than I needed to. After all, I had no reason to believe I was not producing sperm in large enough quantities.

Some men with CF may disagree with me here, especially because lots of people with CF do go for the mTESE, but I felt like the urologist was trying to bill my insurance as high as he could go. In reality, the mTESE is only marginally more successful than the TESE, especially since men with CF do produce sperm. I even had the lab work to conclude with some confidence that I was producing.

Darcy felt the same way after our telehealth consultation, so she asked her fertility doctor if we could chat with a urologist near her Boston area clinic. It was also then when I found out that we would be responsible for transporting the sperm from the extraction to her clinic for study (more on that later).

We were referred to a Boston-based urologist.

Almost immediately the new urologist at Lahey Medical Center validated our thoughts and said that I would not need an mTESE. He was almost shocked that it was even brought up in our previous call. Generally, it’s left in reserve if there’s reason to believe the patient is failing to produce sperm.

As a textbook example of shared decision making, he asked if I would be comfortable doing ultrasound imaging to confirm the presence of sperm before the procedure. I said that I was not in the absence of a vaccine. This all happened in January/February at the height of the case surge. He empathized and instead suggested another blood draw. This time we drew for Inhibin B, which is another marker for sperm production. I fell in the normal range, so the decision was made to proceed. Never shy away from questioning a doctor who seems certain about a choice.

From there, we waited for the vaccine. I did not feel comfortable going into a medical center, no matter how small the procedure, without some protection from a vaccine. My number was called in February. Two weeks later I was scheduled for the TESE biopsy.

We were shocked with how easy it was to schedule the TESE in Boston, compared with how hard it was to get on our original New York-based urologist’s schedule.

As the day inched closer, my fear really started to set in. If you’ve been a long-time reader, you know that I hate needles, shots, sedation and definitely suffer from significant procedural anxiety (and as my wife would say, medical trauma and PTSD). The truth is, the anticipation for the TESE was far worse than the procedure itself. There is just something about being awake on the table while my balls are sliced open. Growing up, enough hockey pucks hit me in the nuts to know that this was going to be unpleasant.

As I have done with every other medical procedure, I took a valium. It helped.

Darcy’s fertility clinic gave us an insulated box containing several test tubes, each filled about halfway with some sort of liquid that was supposed to help preserve my flesh taken during the biopsy. We were instructed to hustle to the fertility clinic quickly after the procedure was completed so they could test the sample and freeze any identified sperm. Not only was I a patient, I was also a courier on this very special day.

The procedure was quite easy. As the urologist explained, “this is a very easy part of the body to numb.” I feel like that’s probably information that should have been shared with me at the very first consultation, but I digress. All in, it lasted about 15 minutes where, among other things, the doctor and I talked about college lacrosse.

When I walked into the filled waiting room to meet Darcy after the fact, I was clearly still under the influence of the valium dose. I proudly proclaimed to the entire waiting room, “THAT WAS SO EASY!” Big smile and all.

There was almost no pain associated with the biopsy whatsoever. In hindsight, I think getting a PICC line is more uncomfortable. The doctor was right, it was an easy part of the body to numb.

The job was finished with a single dissolvable stitch in my right nut.

The drive home, however, was brutal. As the numbing medication began to wear away, each bump we hit on the highway felt like getting struck by a lighting bolt in my balls. After we dropped off the lunchbox containing my flesh with the fertility clinic, I passed out and woke up just before we got home to Hanover. My walk (read: waddle) from the car to the front door, which Darcy documented, felt like the longest 40 feet of my life.

A few hours later, the fertility center called to report that healthy sperm had been extracted.

The search and rescue mission was a success.

(My recovery lasted about a week)