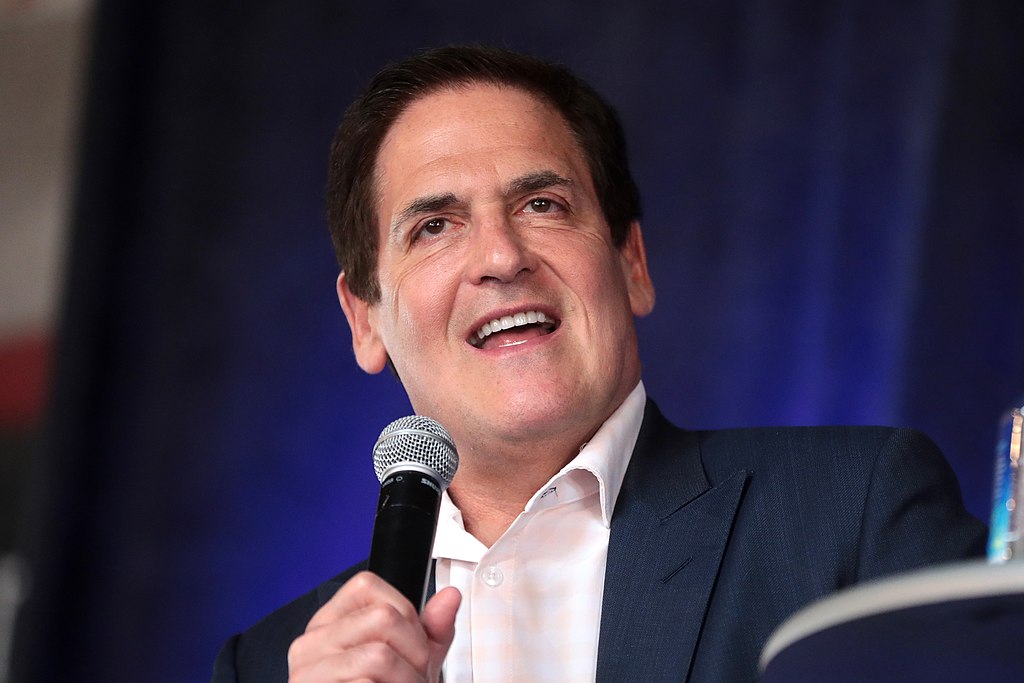

If Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company (yes, that’s literally the name) can be sustained, it might be the welcome relief that can drive generic drug prices down for consumers and reassert the kind of balance Hatch-Waxman had intended to establish when the law was passed in the 1980’s.

The new venture has been all over the news, but what exactly is Cost Plus Drugs?

Essentially it is an online pharmacy (that will also become a manufacturer) that sells generic drugs directly to patients (with a prescription in tow) at the cost of making the drug plus a 15% markup. Importantly, the costs come down because Cuban is cutting out the middlemen – pharmacy benefit managers and health insurance contracts – from the drug supply chain.

This all works in a pretty nuanced way, but to understand how the drug supply chain works, let me provide a little context.

Hatch-Waxman (which I’ve written about on the blog before) provides a period of exclusivity for drug makers that bring novel medications to market before allowing competition to enter the market through generic copies (biosimilars, too, but if you want to learn why that latter class of drug is a little problematic, check out my past blog on the topic).

Essentially, the huge up-front cost to develop a new drug requires a mini-monopoly so drug makers can think about the R&D as a worthwhile investment. Initially after a drug launch, the price the payor pays needs to be high, especially for remarkably effective breakthrough medicines, and market rate (which I stand by), but over time they must crater to generic prices. That 13 or so year drug pricing journey is important for individual products and the market to remain sustainable.

Drug makers not only have to consider the resources they put into a project, but also the projects that don’t get their resources, or the opportunity cost of their choice.

Hatch-Waxman works to protect consumers and payors only when drugs go generic or biosimilar on time. Of course, despite almost 90% of prescriptions coming in generic form, there are other incentives at play that muddy the waters. Some biologic drugs like Humira and Enbrel stand behind patent thickets that delay drug genericization and thus return huge revenues to pharmaceutical companies beyond their intended lifespan. Delaying genericization is wrong. The exclusivity and patent gaming will need to be legislated out of the market.

In other cases, though, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and health benefit plans will actually force the price of generic drugs up so they can get a bigger piece of the pie. Typically it’s called spread pricing, which I’ve also blogged about.

PBMs also charge rebates to drug companies so their drugs can be listed on the formulary. The rebate is essentially a kickback to the PBM that then has to be included in the list price the drug maker charges. You can learn more about that process on the last episode of The State of Health:

Other issues come into play like high-deductible health plans with large out of pocket costs that people get charged when they pick up a prescription at the pharmacy counter. In fact, I blogged about high OOPs last week!

The result of these weird incentives is higher cost for patients, even with insurance benefits. Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company really drives to the core of the problems that legislators are overlooking in the drug supply chain.

In the Company’s press release it was noted, “In November 2021 MCCPDC entered the PBM industry to serve companies providing prescription coverage in their employee benefit plans. MCCPDC has pledged to be “radically transparent” in its own negotiations with drug companies as a PBM, revealing the true costs it pays for drugs and eliminating spread pricing and misaligned rebate incentives.” Further, “The company plans to integrate its pharmacy and wholesaler with its PBM, so any company that uses its PBM will have access to wholesale pricing through its online pharmacy.”

For now, though, the company does not accept insurance, but instead is only all-cash. In most cases the cash price for generic drugs (depending on the insurance benefit a person has), will actually end up being cheaper than the OOP associated with filling a prescription the old fashioned way. The Company lists a few examples:

Notable medications that epitomize the pharmacy’s striking savings include:

- Imatinib – leukemia treatment

- Retail price: $9,657 per month

- Lowest price with common voucher: $120 per month

- MCCPDC price: $47 per month

- Mesalamine – ulcerative colitis treatment

- Retail price: $940 per month

- Lowest price with common voucher: $102 per month

- MCCPDC price: $32.40 per month

- Colchicine – gout treatment

- Retail price: $182 per month

- Lowest price with common voucher: $32 per month

- MCCPDC price: $8.70 per month

My conclusion is this:

When an all-cash pharmacy charges less than the OOP associated with health insurance, health insurance isn’t working correctly.

Importantly, the company is only offering small molecule drugs on generic. So, a notable missing drug is insulin. Mark Cuban noted in a tweet that the company intends not only to be a buy wholesale drugs, but also a maker, which includes injectables. In some ways that’s going to be a whole different can of worms because they are going to have to scale operations to a big enough point where the cost of biosimilar and injectable drugs really does come down substantially. If he succeeds with that plan, he will transform how drugs age overtime, while also allowing society to realize their long term value. It’s my hope that the competition he introduces into the generic and PBM marketplaces will finally pass savings onto patients.